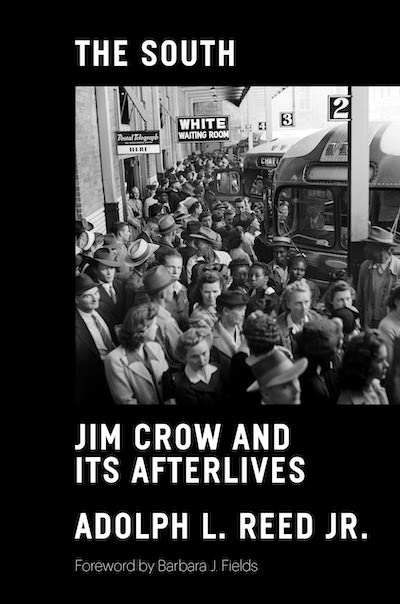

How Long Is the Shadow of Jim Crow?

[ad_1]

WHEN HE WAS in ninth grade, Adolph Reed Jr. stole a bag of chips from a nook retailer in New Orleans. This was in late 1959 or early 1960 (he doesn’t fairly recall), and Reed, like many teenage boys, was in a rebellious part that concerned shoplifting. His flirtation with petty larceny was short-lived — the shopkeepers, a white couple of their 30s, noticed him palming the chips and pulled him apart.

In The South: Jim Crow and Its Afterlives, his memoir-cum-analysis of quotidian life below Jim Crow, Reed recollects the worry he felt when the couple caught him stealing. Like many Black youngsters rising up in Louisiana within the Nineteen Sixties, his household and the encompassing tradition had instilled in him the severity of his state of affairs. The mere accusation of a legal act from a white individual might ship him to the youth reformatory in Baker or, worse, to Angola, the state’s notoriously brutal jail. Fortunately, the couple selected to not inform the police, as an alternative giving Reed a lecture in regards to the risks of stealing and a warning that different shopkeepers may not be so sort.

Nevertheless, Reed notes, the shopkeepers’ choice to subvert the strictures of Jim Crow on this particular occasion reveals little about their total character. That very same couple might have ardently supported the Civil Rights motion, or they might have protested towards college desegregation, which hit New Orleans later that 12 months. “I do know what would make for an uplifting story, however I’ve no illusions,” Reed writes. “All I do know is that, if they’d acted that afternoon in accord with the dictates of the Jim Crow social order and never seen me as they did, I might have, even with the relative insulation of sophistication place, wound up at Baker.”

It’s this skepticism towards uplifting antiracism narratives that makes Reed a controversial determine. All through his profession, Reed has opposed viewing race as a singularly necessary assemble and racism as a historic fixed. This “race reductionism,” as Reed calls it, flattens variations at school standing and hinders the coalitions that convey progressive reforms. In recent times, the destructive results of race reductionism have been aggravated by some elite establishments, which have weaponized race for its revenue potential and averted financial insurance policies which are unpopular with rich donors.

That strategy (and Reed’s penchant for fiery quips) has led to its justifiable share of controversies. In 1996, Reed memorably described Barack Obama as a “easy Harvard lawyer with impeccable do-good credentials and vacuous-to-repressive neoliberal politics.” More moderen targets of his scorn embody “woke tradition” (“irrationalist race reductionism”), the Black Lives Matter group (“careerist race ventriloquists”), and The 1619 Mission (“a big sigh”). Not even the Democratic Socialists of America had been immune: Reed and the New York chapter of the DSA had been pressured to cancel a scheduled discuss after a vocal contingent opposed his politics.

In The South, Reed recounts rising up in New Orleans whereas mixing in his evaluation of segregation. Like his criticisms of Obama or The 1619 Mission, Reed’s views on Jim Crow are each incisive and incendiary. Some sentences, just like the assertion that “[s]egregation was enforced on whites in addition to blacks,” appear tailored to encourage a 280-character retort from sure corners of the left.

The experiences that Reed describes in The South had been core to his ideological formation. Residing on this contradictory system — one by which it might not be stunning for a white shopkeeper to deal with a Black teenager with parental concern someday and lead an anti-integration rally the following — led Reed to oppose drawing a direct line between Jim Crow and modern racial justice points.

Reed argues that those that see Jim Crow as a direct metaphor for the current fall into the lure of race reductionism. When New Orleans determined to take down its monuments to the Confederacy, which had been constructed in the course of the early years of segregation, many lauded the choice as an indication that the symbols of Jim Crow had been toppled. Reed, who occurred to be in New Orleans on the time, recollects feeling pissed off with this logic. Whereas the monuments valorized a despicable period, the choice to take away them was largely performative. Reed writes that it was a “rearguard enterprise” that appeased a neoliberal concept of multiculturalism whereas perpetuating “a social order that’s sharply unequal for many.”

In different phrases, class-based inequality is the historic fixed, not race. Whereas the segregationist order utilized to all Black folks, its impacts had been totally different relying on one’s class. As Reed reminds us, considered one of Homer Plessy’s arguments towards segregated practice vehicles, within the 1896 Supreme Court docket case that enshrined the “separate however equal” doctrine, was that these restrictions denied upper-class Black folks the best to first-class lodging.

Whereas Reed objects to seeing racism as a historic fixed, there are some methods that stay unchanged. Earlier than shifting to New Orleans, Reed lived along with his mother and father in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, the closest city to Cummins State Jail. Throughout Jim Crow, prisoners at Cummins carried out the identical work as their enslaved ancestors, laboring on state-run farms and in municipal buildings with out cost. Reed recollects passing Cummins State Jail on a street journey by way of Arkansas 40 years later:

That day in 1993, by way of the vaporous warmth rising from the dusty soil, we might see off within the distance phalanxes of prisoners of their white uniforms lining up and dealing, overseen by mounted guards with shotguns — precisely as they’d have appeared 4 many years earlier.

These recollections are underpinned by a way of urgency. With every passing 12 months, there are fewer Black Individuals who keep in mind the expertise of residing below Jim Crow. Recollections of the interpersonal relationships — extra human-scale and fewer simple to stage with principle — fade as effectively. In searching for to protect the echoes of those reminiscences, The South follows a protracted report of makes an attempt to know the scars of historical past by way of private expertise.

In the course of the depths of the Despair, the WPA Federal Writers’ Mission despatched writers to gather the tales of previously enslaved folks. Between 1936 and 1938, the Slave Narratives challenge transcribed firsthand accounts from greater than 2,000 Black Southerners. Together with round 500 pictures, these narratives signify probably the most complete makes an attempt to know the expertise of enslaved Black Individuals earlier than they handed away. The Slave Narratives and The South additionally share an immediacy and a specificity that come from the topics’ cautious consideration to their circumstances.

The intentions of the Slave Narratives challenge had been pure, however main flaws within the interviews make it an advanced physique of labor. Whereas there have been a number of Black staff working with the FWP, many of the interviewers who recorded the narratives had been white. In some circumstances, the interviewers had been descendants of landowning households who had enslaved these exact same interviewees. This led topics to wrap their tales in humor or different oblique types of softened communication. Generally, interviewers twisted phrases to suit a nostalgic narrative of the “old-time Negro.”

Reed doesn’t purport to function a spokesman for his era: “I make no declare to generality, a lot much less universality,” he writes. By mining his personal reminiscences of segregation, Reed avoids seeing the previous as a common allegory for the current. The portrait he paints shouldn’t be an easy narrative of progress towards a post-racial future, neither is it a pessimistic lament that sees racial oppression as an unchanging pressure. Moderately, it’s a narrative exploration of a single second in American historical past, as skilled by somebody who lived inside it.

¤

[ad_2]

Source link